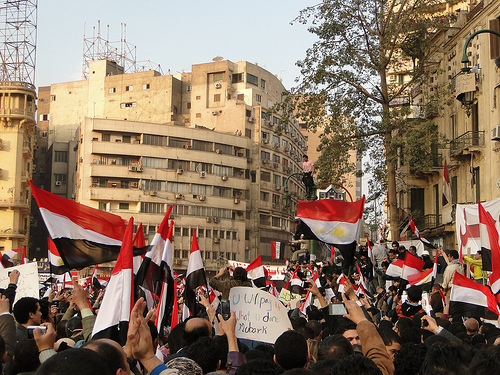

Anti-Morsi protest in Cairo, Egypt, August 2012. Photo credit: Gigi Ibrahim (via Flickr, Creative Commons license).

The recent fall of Egypt’s democratically-elected civilian government is in line with the experiences of many other transitional states attempting to move from authoritarian to democratic rule. As with Egypt’s false start of 2012–2013, transitional states frequently revert back to authoritarian regimes.

In the period between World Wars I and II, over half of the world’s democracies regressed to non-democratic forms of government. After a notable period of decolonization in the mid-twentieth century, the world experienced what Samuel Huntington referred to as another “reverse wave” of democratization in the 1960s. The latter wave of reversals was particularly notable in Africa. Likewise the “third wave of democratization” (from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s) was followed by some notable setbacks, particularly in the post-Soviet region.

The drive for political freedom in the Arab world—possibly including the emergence of liberal democracies—will likely be a generational struggle. The over-reach of the Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo, and a general lack of rule of law—in which the military, courts, and masses are all complicit—do not spell the end of democratic aspirations in this key Arab state.

Humans beings, after all, do learn lessons and recast their behaviors and beliefs. In the wake of the Muslim Brotherhood’s contempt for political compromise and respect for the rule of law, Egyptians must grapple with what to do with a political party that has limited respect for democracy. The military’s ouster of Morsi was distasteful, at best. Perhaps it was the least bad path for Egypt’s future.