This post was written by a guest blogger, Evelyn Robinson

Human suffering and insecurity worldwide is being caused by fragile states and violent conflict, a world leader has said. Finland’s Under-Secretary of State for International Development, Anne Sipilainen, spoke out at the opening of the recent conference into conflict and the post-2015 development agenda in Monrovia, Liberia.

Ms. Sipilainen said more than 1.5 billion people live in countries that are in constant battle with violence and political wrangling. She added that peace processes are being demolished by criminal violence and countries’ inability to generate security, justice and economic development.

The minister said: “Environment suffers, education suffers, the most basic health care cannot be provided, child mortality increases, women are not heard… in this kind of condition, it is very difficult to work on long term development challenges and goals.”

The conference was co-hosted by Liberia and Finland’s governments in the latest United Nation-led push to involve societies in issues surrounding disasters, conflict and security and how a universal framework can be created. A new approach must be taken to see the development of fragile states, Ms. Sipilainen added. Only then would we see the international partners coming together and witness international money transfer, equality and aid across the globe.

Also speaking at the conference, Liberia’s Finance Minister Amara Konneh said almost half of all civil wars and political upheaval in the world between 1990 and 2005 took place in Africa, and its war-related deaths far exceeded all other conflicts in the world. He highlighted the importance for leaders at the conference to agree on how conflict, violence, disaster and fragility hinder development around the world and how solutions must be met.

It is recognized that conflict, violence and disaster are huge obstacles which lie in the way of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) being met in many countries. The eight aims of the MDGs involve: eradicating extreme hunger; universal education; gender equality; child mortality; improving maternal health; combating HIV and AIDS; environment sustainability; and global partnerships.

Are Jobs In Kenya Being Killed By Corruption?

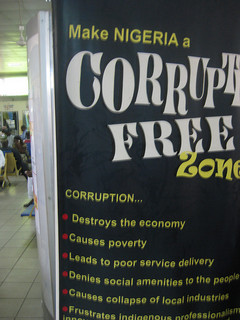

The reality of leaving school with an education only to find there are no jobs is one frustration many young Kenyans have to deal with. But imagine how it must feel to realize that about 250,000 jobs may never be created because of corruption in your country.

The World Bank has revealed in its latest report “Kenya at Work” that the loss of resources at the hands of fraud amount to that quarter of a million number. As the economic climate stands, about 50,000 youths leaving education gain employment, out of a total of 800,000 graduates every year.

The World Bank country director, Johannes Zutt, said: “Nepotism, tribalism, sexual harassment and corruption determine who gets these jobs leaving the rest to find their own means of survival.” The World Bank’s research says firms pay up to 12 per cent value of government contracts in order to win them, and four per cent of their sales goes towards bribes.

The organization concludes total bribes on government contracts are Sh36 billion, while another Sh69 billion is paid in other kickbacks. The report suggests: “Kenya stands out for its high level of business-related corruption.”

The country’s growth is below the African average and substantially below the growth of its neighbors in the East Africa Community. Mr. Zutt said other obstacles in Kenya’s job creation are access to electricity and poor infrastructure. General election shocks and the Euro crisis have left Kenya’s economy in a “stable but vulnerable” state.

The report says: “Kenya’s economy is out of balance and the external position has become even more vulnerable as the country’s current account deficit has skyrocketed and could reach 15 per cent of GDP in 2012. This is among the worst external balances in the world and poses a significant risk to Kenya’s economic stability.”

An imbalance in import and export has struck over the past ten years, as the fragile state’s imports have grown faster than its exports and the top four exports not making enough to pay for oil imports alone. The World Bank report recommends that manufacturing capacity should be boosted. And, critically, Kenya must deal with the negative effects of corruption on farmers.